Granted it wasn't then--and for the most party really still isn't--socially acceptable to be openly and outspokenly unreligious in Renaissance Italy, da Vinci scholars sometimes believe, as sure as they can be of such things across the passage of so much time, that Leonardo da Vinci was possibly an atheist. Or at least, as atheistic as it was possible to get away with being in fifteenth-century Italy, which to us still seems fairly devoutly religious. Other worthies of the day--artists and writers, famous rulers, and others, including Shakespeare--are subject to the same debates and speculation, but da Vinci remains one of the more popular ones, second only to William Shakespeare. In both cases, however, there's an interesting duality at play: both men left for posterity reams of writing, neither of which contains a good amount of detail regarding their personal, private religious and philosophical beliefs. With Shakespeare it's completely impossible to all but loosely speculate what his beliefs might or might not have been as he left no personal missives at all and just eight confirmed works written in his own hand--six signatures (all different, all but two abbreviated), and the words 'by my' accompanying one signature on his will. Da Vinci, by contrast, left volumes and volumes of half a lifetime of scattered thoughts, from observations and studies into the natural world to his scientific researches to notes on every facet of the arts with which he supported himself.

Yet surprisingly little of da Vinci's own words are straightforward and the debate continues over the more private personal thoughts, including his political leanings, personal philosophies, religious leanings, and sexuality. Whether he had any of these at all and what direction they were pointed largely remain a collective question for which there is no certain and straightforward answer. There are, of course, references in his writings to nobilities, the patrons he served, and royalty, and many are in a carefully positive light, but there's a lot of danger in taking this at face value. After all, a lot of the contemporary written accounts of such people as Stalin, the kings of Europe, and Rome's more extreme emperors are also positive but this has less to do with their actual merits and more to do with their ability to have people gruesomely slaughtered for bad publicity. You can't really get a good feel for how people really are based on the words of their subordinates, at least not until comparatively recently.

And so it is with the Vatican and the Catholic Church, particularly from an Italian man at a time when the Church represented far more absolute power than it does today. Pope Julius II famously refused to take Michelangelo's 'NO!' for an answer regarding the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and went as far as to more than once send armies after him and physically drag him back to continue painting (and kept him there for the better part of a decade) when that was the last thing he wanted to do. Not only was refusing or speaking against the Church not allowed--sometimes it was just plain impossible. That da Vinci is known for paintings and sculptures of a religious nature is no more an indicator of his personal religious leanings than a teacher's curriculum is an indicator of their personal tastes--you do what you do to make a living, regardless of your feelings on the matter. (And those who resist this precedent attract attention for it--like Michelangelo, or John Scopes, or any teachers who talk about forbidden subjects like evolution or birth control or banned books--suggesting that silently submitting to authority without consulting your own belief is far more the norm than we're entirely comfortable accepting.)

But, inasmuch as such a thing can be suggested, historians believe that a number of the greater minds of the past might have been something other than dutifully devout--among them da Vinci--and occasionally left clues within their work to leave a secret record of their thoughts for posterity to anyone clever and observant enough to find them. Michelangelo, for example, left a laundry list of secret insults to the Pope and the Church in his famous fresco (including Adam's tiny penis and a cherub giving Pope Julius II a rude hand gesture), though these were undoubtedly more due to his fury at having been forced to paint for eight years rather than any real skepticism.

Da Vinci's surviving works, contemporary accounts, and his famous notebooks offer tantalizing clues about his system of belief, though most are unverifiable. Many people point to his mirror-writing as proof that he was trying to keep his (unpopular and potentially dangerous) thoughts secret, but this doesn't stand up to scrutiny; for one thing, were he that afraid of the repercussions of his words, the smart thing would be to encrypt them or simply not keep record of them at all, and da Vinci was nothing if not smart. Others suggest he was trying to make it harder for others to steal his ideas, but again it falls under the same scrutiny. More likely he simply found it more comfortable to write backwards with his left hand--certainly I do.

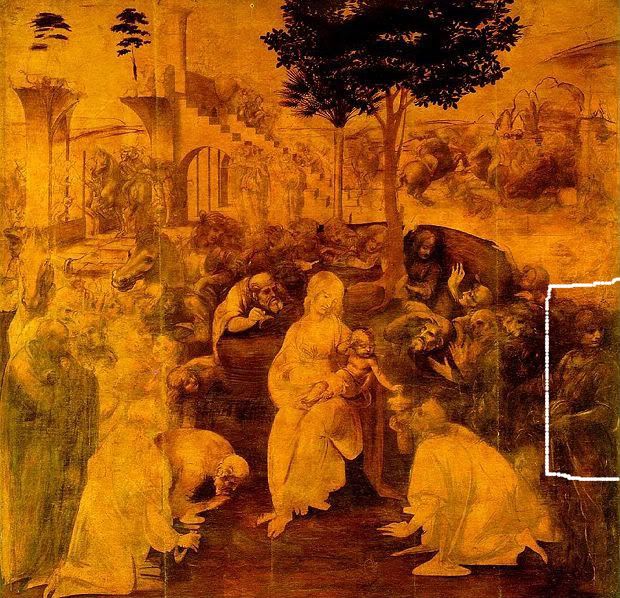

It's been a long time since I've been in school and my memory isn't one of the sturdiest, but I do remember discussing one of da Vinci's earlier paintings. A commission for a coven of Augustinian monks in Florence in 1481, 'The Adoration of the Magi' is the last work he did before taking patronage in Milan and actually left it unfinished (I guess he was pretty anxious to get out of Florence, and ultimately not particularly attached to at least this one painting--allowing speculation abounds regarding how he felt or didn't feel about any of his other masterpieces, including the Mona Lisa). It's a popular Christian subject as far as paintings go--everyone bowing down and worshiping a fat little baby Jesus--and except for being conspicuously incomplete doesn't stand out at all.

There isn't a single striking thing about it. But, if the interpretations are to be believed, a brazenly atheistic da Vinci (who would, at the time, have been about 29--not actually very young at all, and probably considered 'middle aged' or even older for the time) placed a subtle jab at the monks for whom he was working. Purportedly he wasn't terribly happy with the project in the first place--he didn't enjoy religious subjects and didn't like having to spend time around monks--but grudgingly took it for the money. Following some dispute or other with the abbot, he let off a little steam with a little hidden thumb-to-the-nose at not only the Augustinians but also possibly to the Church itself--even though, as insults go, few are more obvious than leaving their painting unfinished and decamping for another city.

Look to the right. The far right, just near the edge. About halfway down. The last young man there on the right. Do you see him?

Right here:

Take a look at him, notice what he's doing. Or, more accurately, notice what he isn't doing.

He is the only (human) person in the painting not looking at the Christ-child. While everyone else fawns and grovels and kisses his feet, the man on the right's attention is elsewhere. He's not just not looking at Jesus--he's looking completely the other way all together. He even looks just the slighted bit smug, and almost like he's getting ready to make his escape and was caught in the frame just as he was going to leave.

There is, naturally, no way of knowing for certain so any interpretation of the piece is just that--interpretation--but it's believed that this is a secret self-portrait of the young da Vinci himself, cheekily showing the world that he couldn't be fucked to give a rat's ass about the baby Jesus. A quiet, but very visible, 'fuck you!' to at least the Augustinian abbot, if not the entire monastery and the Church and religion as a whole--all permanently preserved for the future.

What the real meaning--if any--of this unknown scoffer happens to be, we almost certainly will never know and scholarly discussions regarding him and every other brushstroke and pen-blot da Vinci and his contemporaries ever made will remain forever in open debate. Experts and amateurs alike will always have something to say about it and conclusions to confidently assert.

And whatever da Vinci believed himself, he certainly gives an interesting--if not altogether completely compelling--case one way with a silent jab at religion in one of his many, many paintings.

No comments:

Post a Comment